6.7. Time Series#

This section shows some tools to work with datetime and time series.

6.7.1. Extract Dates from Text with Datefinder#

Show code cell content

!pip install datefinder

Extracting dates from unstructured text can be challenging and time-consuming, especially when the format of the dates varies significantly within the same text:

# Example Input

string_with_dates = """

We have one meeting on May 17th, 2021 at 9:00am

and another meeting on 5/18/2021 at 10:00.

I hope you can attend one of the meetings.

"""

# Traditional string processing to find dates

import re

# Basic regex for dates

pattern = r"(\b\d{1,2}/\d{1,2}/\d{4}\b)|(\b\w+\s\d{1,2}(st|nd|rd|th)?,\s\d{4}\b)"

matches = re.findall(pattern, string_with_dates)

print(

f"Matches: {[match[0] or match[1] for match in matches]}"

) # Limited and inflexible

Matches: ['May 17th, 2021', '5/18/2021']

Datefinder simplifies the process of identifying and extracting dates from text, even when the formats vary:

import datefinder

# Example Input

string_with_dates = """

We have one meeting on May 17th, 2021 at 9:00am

and another meeting on 5/18/2021 at 10:00.

I hope you can attend one of the meetings.

"""

# Extract dates from text

matches = datefinder.find_dates(string_with_dates)

## Print each match

for match in matches:

print(match)

import datefinder

# Example Input

string_with_dates = """

We have one meeting on May 17th, 2021 at 9:00am

and another meeting on 5/18/2021 at 10:00.

I hope you can attend one of the meetings.

"""

## Extract dates from text

matches = datefinder.find_dates(string_with_dates)

## Print each match

for match in matches:

print(match)

2021-05-17 09:00:00

2021-05-18 10:00:00

In the above code:

datefinder.find_dates()- This function identifies potential date strings in the input text and converts them intodatetimeobjects.string_with_dates- Text containing dates in multiple formats.matches- An iterator returning each located date as adatetimeobject.

6.7.2. Fastai’s add_datepart: Add Relevant DateTime Features in One Line of Code#

Show code cell content

!pip install fastai

Time series analysis often benefits from date-based features like year, month, and day of week. Fastai’s add_datepart method generates these features in one line of code, simplifying data preparation.

from datetime import datetime

import pandas as pd

from fastai.tabular.core import add_datepart

df = pd.DataFrame(

{

"date": [

datetime(2020, 2, 5),

datetime(2020, 2, 6),

datetime(2020, 2, 7),

datetime(2020, 2, 8),

],

"val": [1, 2, 3, 4],

}

)

df

| date | val | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2020-02-05 | 1 |

| 1 | 2020-02-06 | 2 |

| 2 | 2020-02-07 | 3 |

| 3 | 2020-02-08 | 4 |

df = add_datepart(df, "date")

df.columns

Index(['val', 'Year', 'Month', 'Week', 'Day', 'Dayofweek', 'Dayofyear',

'Is_month_end', 'Is_month_start', 'Is_quarter_end', 'Is_quarter_start',

'Is_year_end', 'Is_year_start', 'Elapsed'],

dtype='object')

6.7.3. Maya: Convert the string to datetime automatically#

Show code cell content

!pip install maya

Date string conversion to datetime can be tedious using strptime(). The maya library simplifies this process by automatically parsing date strings without needing to specify the format.

import maya

## Automatically parse datetime string

string = "2016-12-16 18:23:45.423992+00:00"

maya.parse(string).datetime()

datetime.datetime(2016, 12, 16, 18, 23, 45, 423992, tzinfo=<UTC>)

Better yet, if you want to convert the string to a different time zone (for example, CST), you can parse that into maya’s datetime function.

maya.parse(string).datetime(to_timezone="US/Central")

datetime.datetime(2016, 12, 16, 12, 23, 45, 423992, tzinfo=<DstTzInfo 'US/Central' CST-1 day, 18:00:00 STD>)

6.7.4. Pendulum: Python Datetimes Made Easy#

Show code cell content

!pip install pendulum

While native datetime instances are sufficient for simple cases, they can become difficult to work with when dealing with more complex scenarios.

Conversely, Pendulum offers a more intuitive and user-friendly API, making it a convenient drop-in replacement for the standard datetime class.

The examples below demonstrate the syntax differences between using the standard datetime library and Pendulum.

Datetime:

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

import pytz

## Creating a datetime

now = datetime.now()

print(f"Current time: {now}")

## Date arithmetic

future = now + timedelta(days=7)

print(f"7 days from now: {future}")

## Timezone handling

utc_now = datetime.now(pytz.UTC)

tokyo_tz = pytz.timezone("Asia/Tokyo")

tokyo_time = utc_now.astimezone(tokyo_tz)

print(f"Time in Tokyo: {tokyo_time}")

## Parsing (requires exact format)

parsed = datetime.strptime("2023-05-15 14:30:00", "%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

## Time difference (not human-readable)

diff = parsed - now

print(f"Difference: {diff}")

Current time: 2024-09-02 19:18:13.589774

7 days from now: 2024-09-09 19:18:13.589774

Time in Tokyo: 2024-09-03 09:18:13.590063+09:00

Difference: -477 days, 19:11:46.410226

Pendulum:

import pendulum

## Creating a datetime

now = pendulum.now()

print(f"Current time: {now}")

## Date arithmetic (more intuitive than datetime)

future = now.add(days=7)

print(f"7 days from now: {future}")

## Timezone handling

tokyo_time = now.in_timezone("Asia/Tokyo")

print(f"Time in Tokyo: {tokyo_time}")

## Parsing without specifying format

parsed = pendulum.parse("2023-05-15 14:30:00")

print(f"Parsed date: {parsed}")

## Human-readable differences

diff = parsed - now

print(f"Difference: {diff.in_words()}")

Current time: 2024-09-02 18:58:20.467988-05:00

7 days from now: 2024-09-09 18:58:20.467988-05:00

Time in Tokyo: 2024-09-03 08:58:20.467988+09:00

Parsed date: 2023-05-15 14:30:00+00:00

Difference: -1 year -3 months -2 weeks -4 days -9 hours -28 minutes -20 seconds

6.7.5. traces: A Python Library for Unevenly-Spaced Time Series Analysis#

Show code cell content

!pip install traces

To analyze unevenly-spaced time series, you can use the traces library. It allows you to infer missing values in your time series based on the data you already have.

Here’s an example where we log working hours for several dates but miss a few:

## Log working hours for each date

from datetime import datetime

import traces

working_hours = traces.TimeSeries()

working_hours[datetime(2021, 9, 10)] = 10

working_hours[datetime(2021, 9, 12)] = 5

working_hours[datetime(2021, 9, 13)] = 6

working_hours[datetime(2021, 9, 16)] = 2

To retrieve the hours for dates where no data was logged, traces fills in the gaps using neighboring values:

## Get value on 2021/09/11

working_hours[datetime(2021, 9, 11)]

10

## Get value on 2021/09/14

working_hours[datetime(2021, 9, 14)]

6

You can also calculate the distribution of working hours over a range of dates:

distribution = working_hours.distribution(

start=datetime(2021, 9, 10), end=datetime(2021, 9, 16)

)

distribution

Histogram({5: 0.16666666666666666, 6: 0.5, 10: 0.3333333333333333})

From this, we can infer that 50% of the time, 6 hours were logged per day.

To get the median and mean working hours across the range:

distribution.median()

6.0

distribution.mean()

7.166666666666666

6.7.6. Extract holiday from date column#

Show code cell content

!pip install holidays

To identify holidays from a date, use the holidays package. This package offers a dictionary of holidays for various countries.

The following code checks if “2020-07-04” is a US holiday and retrieves its name:

from datetime import date

import holidays

us_holidays = holidays.UnitedStates()

"2014-07-04" in us_holidays

True

The package handles various date formats:

us_holidays.get("2014-7-4")

'Independence Day'

us_holidays.get("2014/7/4")

'Independence Day'

6.7.7. Workalendar: Handle Working-Day Computation in Python#

Show code cell content

!pip install workalendar

To manage calendars, holidays, and working-day computations, use the workalendar package. It supports nearly 100 countries worldwide.

from datetime import date

from workalendar.asia import Japan

from workalendar.usa import UnitedStates

## Get all holidays in the US

US_cal = UnitedStates()

US_cal.holidays(2024)

[(datetime.date(2024, 1, 1), 'New year'),

(datetime.date(2024, 1, 15), 'Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr.'),

(datetime.date(2024, 2, 19), "Washington's Birthday"),

(datetime.date(2024, 5, 27), 'Memorial Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 7, 4), 'Independence Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 9, 2), 'Labor Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 10, 14), 'Columbus Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 11, 11), 'Veterans Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 11, 28), 'Thanksgiving Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 12, 25), 'Christmas Day')]

US_cal.is_working_day(date(2024, 9, 15)) # Sunday

False

US_cal.is_working_day(date(2024, 9, 2)) # Labor Day

False

## Calculate working days between 2024/1/19 and 2024/5/15

US_cal.get_working_days_delta(date(2024, 1, 19), date(2024, 5, 15))

82

## Get holidays in Japan

JA_cal = Japan()

JA_cal.holidays(2024)

[(datetime.date(2024, 1, 1), 'New year'),

(datetime.date(2024, 1, 8), 'Coming of Age Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 2, 11), 'Foundation Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 2, 23), "The Emperor's Birthday"),

(datetime.date(2024, 3, 20), 'Vernal Equinox Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 4, 29), 'Showa Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 5, 3), 'Constitution Memorial Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 5, 4), 'Greenery Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 5, 5), "Children's Day"),

(datetime.date(2024, 7, 15), 'Marine Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 8, 11), 'Mountain Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 9, 16), 'Respect-for-the-Aged Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 9, 22), 'Autumnal Equinox Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 10, 14), 'Sports Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 11, 3), 'Culture Day'),

(datetime.date(2024, 11, 23), 'Labour Thanksgiving Day')]

6.7.8. Pmdarima: Harness R’s auto.arima Power with a scikit-learn-Like Interface#

Show code cell content

!pip install pmdarima

To achieve functionality similar to R’s auto.arima within a scikit-learn-like interface, use Pmdarima.

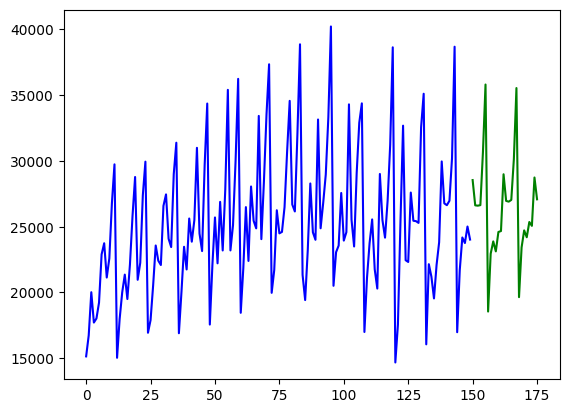

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pmdarima as pm

from pmdarima.model_selection import train_test_split

## Load/split your data

y = pm.datasets.load_wineind()

train, test = train_test_split(y, train_size=150)

## Fit your model

model = pm.auto_arima(train, seasonal=True, m=12)

## Make your forecasts

forecasts = model.predict(test.shape[0]) # predict N steps into the future

## Visualize the forecasts (blue=train, green=forecasts)

x = np.arange(y.shape[0])

plt.plot(x[:150], train, c="blue")

plt.plot(x[150:], forecasts, c="green")

plt.show()

Fitting a more complex pipeline on the sunspots dataset, serializing it, and then loading it from disk to make predictions:

import pickle

import pmdarima as pm

from pmdarima.model_selection import train_test_split

from pmdarima.pipeline import Pipeline

from pmdarima.preprocessing import BoxCoxEndogTransformer

## Load/split your data

y = pm.datasets.load_sunspots()

train, test = train_test_split(y, train_size=2700)

## Define and fit your pipeline

pipeline = Pipeline(

[

("boxcox", BoxCoxEndogTransformer(lmbda2=1e-6)),

(

"arima",

pm.AutoARIMA(seasonal=True, m=12, suppress_warnings=True, trace=True),

),

]

)

pipeline.fit(train)

# Serialize your model just like you would in scikit:

with open("model.pkl", "wb") as pkl:

pickle.dump(pipeline, pkl)

## Load it and make predictions seamlessly:

with open("model.pkl", "rb") as pkl:

mod = pickle.load(pkl)

print(mod.predict(15))

Performing stepwise search to minimize aic

ARIMA(2,1,2)(1,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=inf, Time=6.52 sec

ARIMA(0,1,0)(0,0,0)[12] intercept : AIC=10383.210, Time=0.04 sec

ARIMA(1,1,0)(1,0,0)[12] intercept : AIC=10020.218, Time=0.80 sec

ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9831.422, Time=1.11 sec

ARIMA(0,1,0)(0,0,0)[12] : AIC=10381.212, Time=0.05 sec

ARIMA(0,1,1)(0,0,0)[12] intercept : AIC=9830.357, Time=0.12 sec

ARIMA(0,1,1)(1,0,0)[12] intercept : AIC=9831.459, Time=0.70 sec

ARIMA(0,1,1)(1,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9831.930, Time=3.67 sec

ARIMA(1,1,1)(0,0,0)[12] intercept : AIC=9817.480, Time=0.22 sec

ARIMA(1,1,1)(1,0,0)[12] intercept : AIC=9817.508, Time=1.15 sec

ARIMA(1,1,1)(0,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9817.413, Time=2.34 sec

ARIMA(1,1,1)(1,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9817.657, Time=3.29 sec

ARIMA(1,1,1)(0,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=9817.996, Time=4.25 sec

ARIMA(1,1,1)(1,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=9820.047, Time=4.23 sec

ARIMA(1,1,0)(0,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=10020.213, Time=0.82 sec

ARIMA(2,1,1)(0,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9817.896, Time=2.30 sec

ARIMA(1,1,2)(0,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9818.625, Time=2.49 sec

ARIMA(0,1,0)(0,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=10385.194, Time=0.98 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(0,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9816.628, Time=1.55 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(0,0,0)[12] intercept : AIC=9816.710, Time=0.41 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(1,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9816.881, Time=4.06 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(0,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=9817.222, Time=3.11 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(1,0,0)[12] intercept : AIC=9816.722, Time=1.20 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(1,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=9813.247, Time=10.18 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(2,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=inf, Time=19.62 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(2,0,1)[12] intercept : AIC=9819.401, Time=3.04 sec

ARIMA(0,1,1)(1,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=9834.327, Time=3.96 sec

ARIMA(1,1,2)(1,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=9815.242, Time=17.06 sec

ARIMA(0,1,3)(1,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=9815.236, Time=15.52 sec

ARIMA(1,1,3)(1,0,2)[12] intercept : AIC=9816.564, Time=23.76 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(1,0,2)[12] : AIC=9811.253, Time=6.00 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(0,0,2)[12] : AIC=9815.230, Time=1.26 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(1,0,1)[12] : AIC=9814.890, Time=1.09 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(2,0,2)[12] : AIC=inf, Time=9.39 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(0,0,1)[12] : AIC=9814.636, Time=0.61 sec

ARIMA(0,1,2)(2,0,1)[12] : AIC=9817.409, Time=1.12 sec

ARIMA(0,1,1)(1,0,2)[12] : AIC=9832.334, Time=1.30 sec

ARIMA(1,1,2)(1,0,2)[12] : AIC=9813.248, Time=5.01 sec

ARIMA(0,1,3)(1,0,2)[12] : AIC=9813.242, Time=4.11 sec

ARIMA(1,1,1)(1,0,2)[12] : AIC=9818.055, Time=1.73 sec

ARIMA(1,1,3)(1,0,2)[12] : AIC=9814.546, Time=8.53 sec

Best model: ARIMA(0,1,2)(1,0,2)[12]

Total fit time: 178.878 seconds

[26.73630214 26.72738664 27.33806937 27.97670263 26.94336951 27.27600697

26.76335004 27.06207145 28.18910652 27.76778119 28.01474934 27.41947969

27.57286429 27.30950555 27.63971231]

6.7.9. aeon: The Ultimate Library for Time-Series Forecasting and Classification#

Show code cell content

!pip install aeon

aeon is a library for time-series data that is compatible with scikit-learn and offers a variety of advanced algorithms for learning tasks like forecasting and classification.

import pandas as pd

from aeon.forecasting.trend import TrendForecaster

y = pd.Series([20.0, 40.0, 60.0, 80.0, 100.0])

forecaster = TrendForecaster()

# fit the forecaster

forecaster.fit(y)

# forecast the next 3 values

forecaster.predict(fh=[1, 2, 3])

5 120.0

6 140.0

7 160.0

dtype: float64

import numpy as np

from aeon.classification.distance_based import KNeighborsTimeSeriesClassifier

# 3 samples and 6 time steps

X = np.array([[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 5], [1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 2], [8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 4]])

# class labels for each sample

y = np.array(["low", "low", "high"])

## Define the classifier

clf = KNeighborsTimeSeriesClassifier(distance="dtw")

# fit the classifier on train data

clf.fit(X, y)

## Test data

X_test = np.array([[2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2], [6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6]])

## Make class predictions on new data

y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

y_pred

array(['low', 'high'], dtype='<U4')

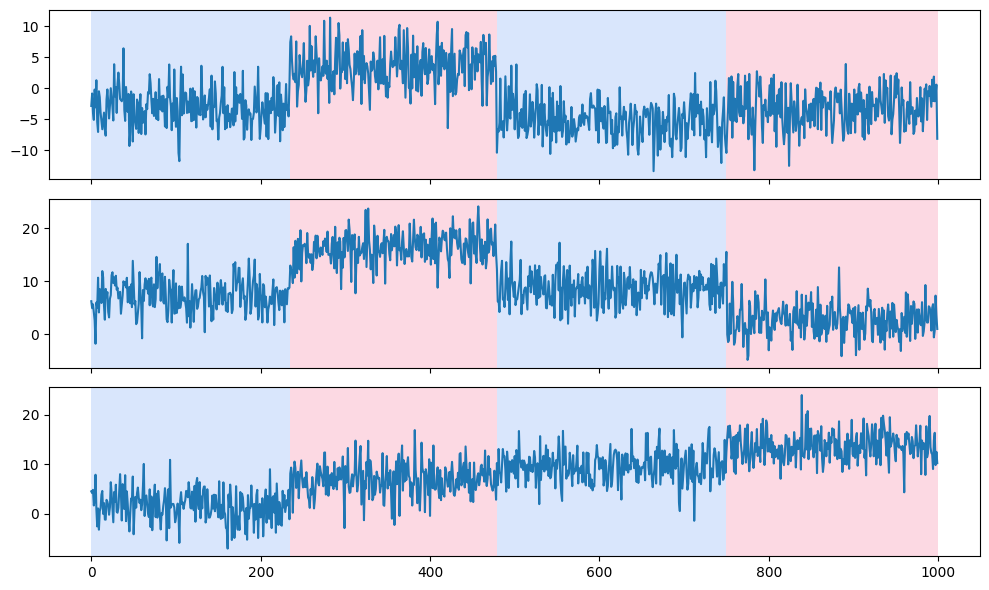

6.7.10. Ruptures: Detecting Change Points in Non-Stationary Signals#

Show code cell content

!pip install ruptures

Use ruptures to detect change points from non-stationary signals such as trend, seasonality, and variance.

With change points, you can detect anomalies or deviations from the expected behavior and gain insights into when these transitions occur.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import ruptures as rpt

# generate signal

n_samples, n_features, sigma = 1000, 3, 3

num_breakpoints = 3

signal, true_breakpoints = rpt.pw_constant(

n_samples, n_features, num_breakpoints, noise_std=sigma

)

# detection

algo = rpt.Pelt(model="rbf").fit(signal)

predicted_breakpoints = algo.predict(pen=10)

# display

rpt.display(signal, predicted_breakpoints)

plt.show()

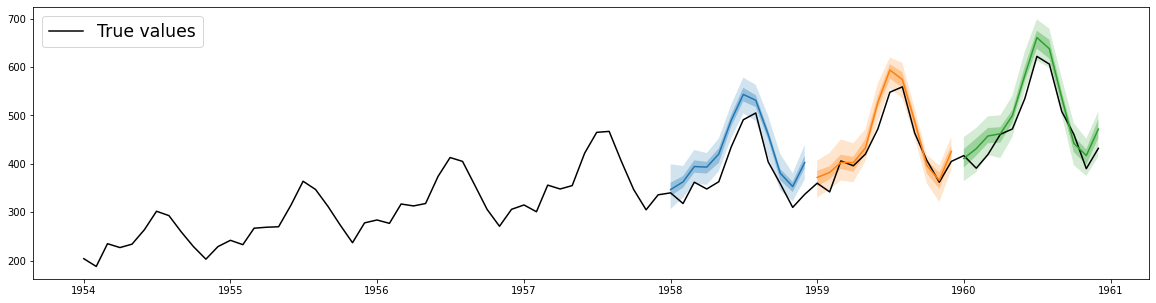

6.7.11. GluonTS: Probabilistic Time Series Modeling in Python#

Probabilistic models offer a range of possible future outcomes, rather than a single fixed prediction, allowing for the assessment of risk associated with adverse events.

GluonTS streamlines the process of using probabilistic models for time series data.

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from gluonts.dataset.pandas import PandasDataset

from gluonts.dataset.split import split

from gluonts.torch import DeepAREstimator

## Load data from a CSV file into a PandasDataset

df = pd.read_csv(

"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/AileenNielsen/"

"TimeSeriesAnalysisWithPython/master/data/AirPassengers.csv",

index_col=0,

parse_dates=True,

)

dataset = PandasDataset(df, target="#Passengers")

## Split the data for training and testing

training_data, test_gen = split(dataset, offset=-36)

test_data = test_gen.generate_instances(prediction_length=12, windows=3)

## Train the model and make predictions

model = DeepAREstimator(

prediction_length=12, freq="M", trainer_kwargs={"max_epochs": 5}

).train(training_data)

forecasts = list(model.predict(test_data.input))

## Plot predictions

plt.plot(df["1954":], color="black")

for forecast in forecasts:

forecast.plot()

plt.legend(["True values"], loc="upper left", fontsize="xx-large")

plt.show()

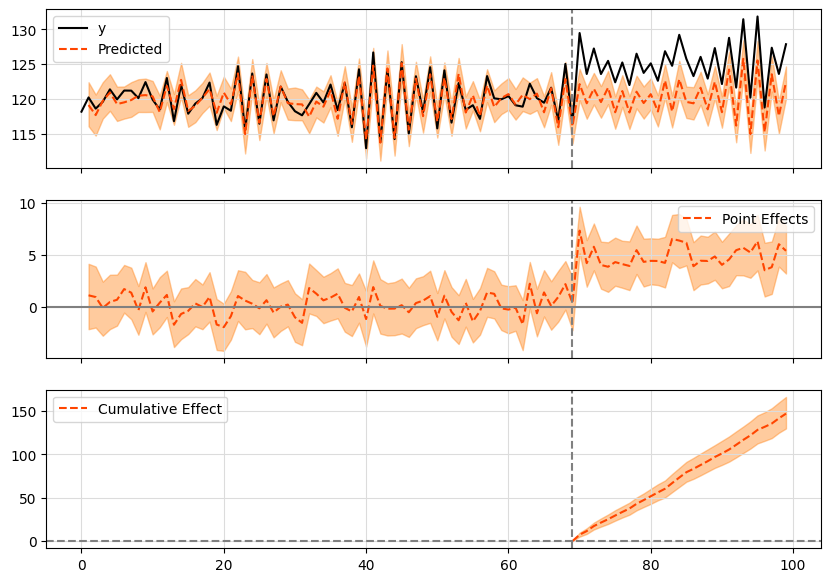

6.7.12. tfcausalimpact: Understand Causal Relationships in Time Series Data#

Show code cell content

!pip install tfcausalimpact

You’re running a marketing campaign and see a user increase. But how do you know if it’s due to the campaign or just a coincidence?

That is when tfcausalimpact comes in handy. It forecasts future data trends using a Bayesian structural model and compares them to actual data to give you meaningful insights.

import pandas as pd

from causalimpact import CausalImpact

data = pd.read_csv(

"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/WillianFuks/tfcausalimpact/master/tests/fixtures/arma_data.csv"

)[["y", "X"]]

data.iloc[70:, 0] += 5

ci = CausalImpact(data, pre_period=[0, 69], post_period=[70, 99])

print(ci.summary())

print(ci.summary(output="report"))

ci.plot()

Posterior Inference {Causal Impact} Average Cumulative Actual 125.23 3756.86 Prediction (s.d.) 120.33 (0.3) 3609.94 (9.11) 95% CI [119.75, 120.94] [3592.64, 3628.34]

Absolute effect (s.d.) 4.9 (0.3) 146.93 (9.11) 95% CI [4.28, 5.47] [128.52, 164.23]

Relative effect (s.d.) 4.07% (0.25%) 4.07% (0.25%) 95% CI [3.56%, 4.55%] [3.56%, 4.55%]

Posterior tail-area probability p: 0.0 Posterior prob. of a causal effect: 100.0%

For more details run the command: print(impact.summary('report'))

Analysis report {CausalImpact}

During the post-intervention period, the response variable had an average value of approx. 125.23. By contrast, in the absence of an intervention, we would have expected an average response of 120.33. The 95% interval of this counterfactual prediction is [119.75, 120.94]. Subtracting this prediction from the observed response yields an estimate of the causal effect the intervention had on the response variable. This effect is 4.9 with a 95% interval of [4.28, 5.47]. For a discussion of the significance of this effect, see below.

Summing up the individual data points during the post-intervention period (which can only sometimes be meaningfully interpreted), the response variable had an overall value of 3756.86. By contrast, had the intervention not taken place, we would have expected a sum of 3609.94. The 95% interval of this prediction is [3592.64, 3628.34].

The above results are given in terms of absolute numbers. In relative terms, the response variable showed an increase of +4.07%. The 95% interval of this percentage is [3.56%, 4.55%].

This means that the positive effect observed during the intervention period is statistically significant and unlikely to be due to random fluctuations. It should be noted, however, that the question of whether this increase also bears substantive significance can only be answered by comparing the absolute effect (4.9) to the original goal of the underlying intervention.

The probability of obtaining this effect by chance is very small (Bayesian one-sided tail-area probability p = 0.0). This means the causal effect can be considered statistically significant.

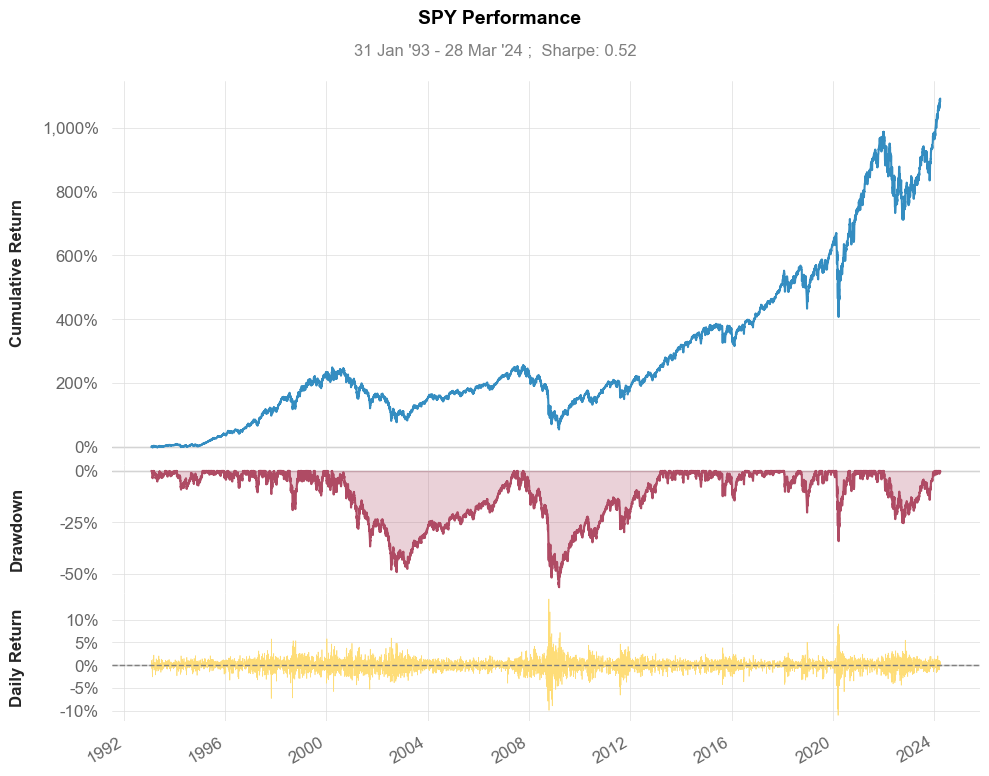

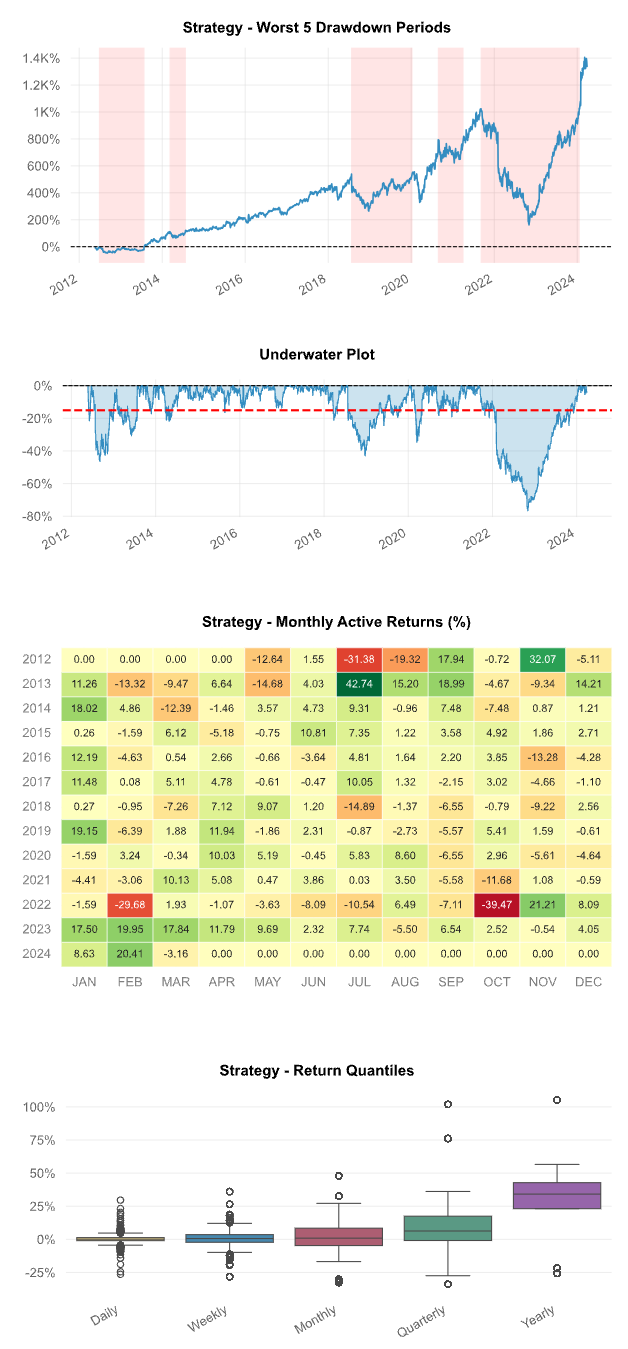

6.7.13. QuantStats: Simplify Stock Performance Analysis in Python#

Show code cell content

!pip install quantstats

To visualize and analyze the performance of specific stocks using just a few lines of Python, try QuantStats.

The code below shows how to use QuantStats to visualize stock performance.

import quantstats as qs

qs.extend_pandas()

# fetch the daily returns for a stock

stock = qs.utils.download_returns("SPY")

# visualize stock performance

qs.plots.snapshot(stock, title="SPY Performance", show=True)

[*********************100%%**********************] 1 of 1 completed

qs.reports.html(stock, "SPY")

Running the code above will generate a report that looks similar to this:

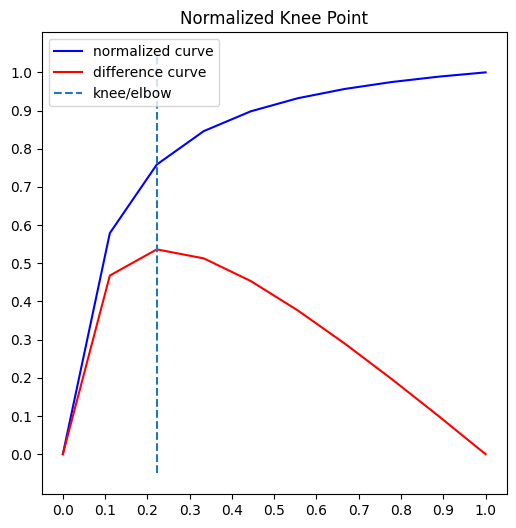

6.7.14. kneed: Knee-Point Detection in Time Series#

Show code cell content

!pip install "kneed[plot]"

Knee-point detection in time series identifies the point of maximum curvature. The knee point can identify anomalies or outliers in the time series. If a data point is far away from the knee point, it may indicate an anomaly or unexpected behavior.

The kneed library makes it easy to implement knee-point detection in Python.

from kneed import DataGenerator, KneeLocator

x, y = DataGenerator.figure2()

kneedle = KneeLocator(x, y, S=1.0, curve="concave", direction="increasing")

kneedle.plot_knee_normalized()

6.7.15. Visualize Time Series with plot_series#

Show code cell content

!pip install utilsforecast

Analyzing time series data and forecasts can be challenging without proper visualization. Raw data often lacks context or insights, making it difficult to interpret trends, anomalies, and forecast accuracy effectively.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# Example of a simple time series dataset

np.random.seed(42)

date_range = pd.date_range(start="2023-01-01", periods=30, freq="D")

data = {

"unique_id": ["id_1"] * 30,

"ds": date_range,

"y": np.random.randn(30).cumsum(), # Simulating cumulative values

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

## Plotting without any framework - raw visualization

plt.plot(df["ds"], df["y"], label="Observed Values")

plt.xlabel("Date")

plt.ylabel("Value")

plt.title("Raw Time Series Visualization")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

plot_series from Nixtla’s utilsforecast offers advanced and customizable plotting capabilities for time series data, enabling clear visualization of forecasts, anomalies, and prediction intervals.

Utilize plot_series to visualize time series data and forecasts using the following steps:

6.7.16. Preparing the Data#

generate_series is a utility to simulate time series data, including training and testing datasets. Below, we create a dataset with 4 time series, each containing a trend, and split it into training and testing sets.

from utilsforecast.data import generate_series

## Generate example time series data

level = [80, 95] # Confidence intervals

series = generate_series(

n_series=1, # Number of time series

freq="D", # Daily frequency

equal_ends=True,

with_trend=True,

n_models=2, # Number of forecast models

level=level,

)

## Split data into training and testing

test_pd = series.groupby("unique_id", observed=True).tail(10).copy()

train_pd = series.drop(test_pd.index)

6.7.17. Visualizing Using plot_series#

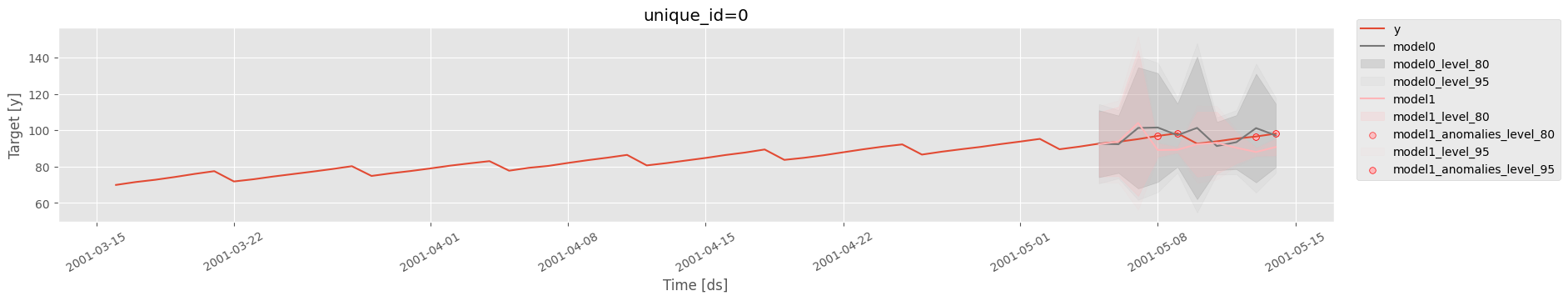

We utilize the plot_series function to visualize both the training and forecasted data for selected time series.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from utilsforecast.plotting import plot_series

## Style for plots

plt.style.use("ggplot")

## Plot using plot_series

fig = plot_series(

train_pd, # Training dataset

forecasts_df=test_pd, # Forecast dataset

ids=[0], # Select specific time series to plot

plot_random=False, # Ensure reproducibility

level=level, # Add prediction intervals

max_insample_length=50, # Limit insample length

engine="matplotlib", # Use matplotlib for visualization

plot_anomalies=True, # Highlight anomalies

)

fig

The generated plot includes:

The actual observed values from the training dataset.

Forecasted values for the testing dataset.

Highlighted anomalies (if any) based on prediction intervals.

Confidence intervals (80% and 95%) for forecasted data.

The output reveals the time series trends, forecasts, and anomalies. Confidence intervals provide clarity on the uncertainty of predictions, while anomalies indicate deviations from expected patterns.

6.7.18. NeuralForecast: Streamline Neural Forecasting with Familiar Sklearn Syntax#

Show code cell content

pip install neuralforecast

Neural forecasting methods can enhance the accuracy of forecasting, but they are often difficult to use and computationally expensive.

NeuralForecast provides a simple way to use proven accurate and efficient models, using familiar sklearn syntax. The models available in NeuralForecast range from classic networks like RNN to the latest transformers.

from neuralforecast import NeuralForecast

from neuralforecast.models import NBEATS

from neuralforecast.utils import AirPassengersDF

nf = NeuralForecast(models=[NBEATS(input_size=24, h=12, max_steps=100)], freq="M")

nf.fit(df=AirPassengersDF)

nf.predict()

6.7.19. Scaling Time-Series Forecasting with StatsForecast and Spark#

Show code cell content

!pip install statsforecast pyspark

Traditional time series libraries are typically built to run in-memory on single machines, which poses challenges when handling extremely large datasets.

StatsForecast, however, provides seamless compatibility with Spark, allowing users to perform scalable and efficient time-series forecasting on large datasets directly within Spark.

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

spark = SparkSession.builder.config(

"spark.executorEnv.NIXTLA_ID_AS_COL", "1"

).getOrCreate()

from statsforecast.core import StatsForecast

from statsforecast.models import AutoETS

from statsforecast.utils import generate_series

from tqdm.autonotebook import tqdm

n_series = 4

horizon = 7

series = generate_series(n_series)

## Convert to Spark

spark_df = spark.createDataFrame(series)

spark_df.show(5)

/Users/khuyentran/.pyenv/versions/3.8.16/lib/python3.8/site-packages/statsforecast/core.py:27: TqdmExperimentalWarning: Using `tqdm.autonotebook.tqdm` in notebook mode. Use `tqdm.tqdm` instead to force console mode (e.g. in jupyter console)

from tqdm.autonotebook import tqdm

+---------+-------------------+-------------------+

|unique_id| ds| y|

+---------+-------------------+-------------------+

| 0|2000-01-01 00:00:00|0.30138168803582194|

| 0|2000-01-02 00:00:00| 1.2724415914984484|

| 0|2000-01-03 00:00:00| 2.211827399669452|

| 0|2000-01-04 00:00:00| 3.322947056533328|

| 0|2000-01-05 00:00:00| 4.218793605631347|

+---------+-------------------+-------------------+

only showing top 5 rows

sf = StatsForecast(models=[AutoETS(season_length=7)], freq="D")

## Returns a Spark DataFrame

sf.forecast(df=spark_df, h=horizon, level=[90]).show(5)

6.7.20. Beyond Point Estimates: Leverage Prediction Intervals for Robust Forecasting#

Show code cell content

!pip install mlforecast utilsforecast

Generating a forecast typically produces a single point estimate, which does not reflect the uncertainty associated with the prediction.

To quantify this uncertainty, we need prediction intervals - a range of values the forecast can take with a given probability. MLForecast allows you to train sklearn models to generate both point forecasts and prediction intervals.

To demonstrate this, let’s consider the following example:

import pandas as pd

from utilsforecast.plotting import plot_series

train = pd.read_csv("https://auto-arima-results.s3.amazonaws.com/M4-Hourly.csv")

test = pd.read_csv("https://auto-arima-results.s3.amazonaws.com/M4-Hourly-test.csv")

train.head()

| unique_id | ds | y | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | H1 | 1 | 605.0 |

| 1 | H1 | 2 | 586.0 |

| 2 | H1 | 3 | 586.0 |

| 3 | H1 | 4 | 559.0 |

| 4 | H1 | 5 | 511.0 |

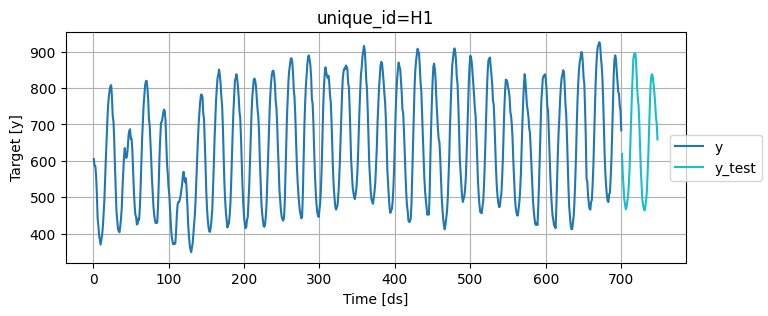

We’ll only use the first series of the dataset.

n_series = 1

uids = train["unique_id"].unique()[:n_series]

train = train.query("unique_id in @uids")

test = test.query("unique_id in @uids")

Plot these series using the plot_series function from the utilsforecast library

fig = plot_series(

df=train,

forecasts_df=test.rename(columns={"y": "y_test"}),

models=["y_test"],

palette="tab10",

)

fig.set_size_inches(8, 3)

fig

Train multiple models that follow the sklearn syntax:

from mlforecast import MLForecast

from mlforecast.target_transforms import Differences

from mlforecast.utils import PredictionIntervals

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsRegressor

mlf = MLForecast(

models=[

LinearRegression(),

KNeighborsRegressor(),

],

freq=1,

target_transforms=[Differences([1])],

lags=[24 * (i + 1) for i in range(7)],

)

Apply the feature engineering and train the models:

mlf.fit(

df=train,

prediction_intervals=PredictionIntervals(n_windows=10, h=48),

)

MLForecast(models=[LinearRegression, KNeighborsRegressor], freq=1, lag_features=['lag24', 'lag48', 'lag72', 'lag96', 'lag120', 'lag144', 'lag168'], date_features=[], num_threads=1)

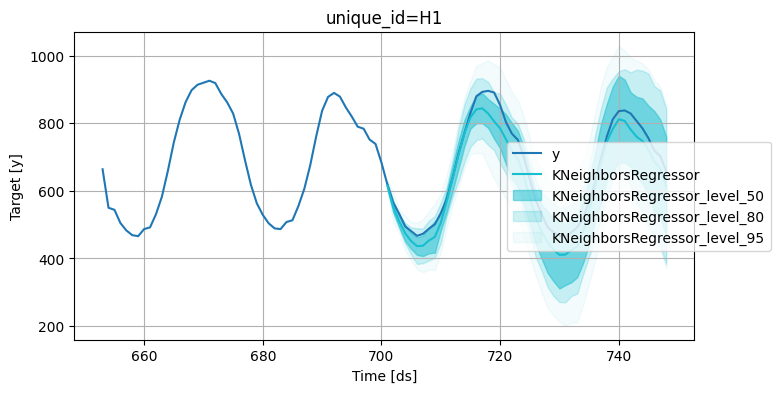

Generate forecasts with prediction intervals:

## A list of floats with the confidence levels of the prediction intervals

levels = [50, 80, 95]

## Predict the next 48 hours

horizon = 48

## Generate forecasts with prediction intervals

forecasts = mlf.predict(h=horizon, level=levels)

forecasts.head()

| unique_id | ds | LinearRegression | KNeighborsRegressor | LinearRegression-lo-95 | LinearRegression-lo-80 | LinearRegression-lo-50 | LinearRegression-hi-50 | LinearRegression-hi-80 | LinearRegression-hi-95 | KNeighborsRegressor-lo-95 | KNeighborsRegressor-lo-80 | KNeighborsRegressor-lo-50 | KNeighborsRegressor-hi-50 | KNeighborsRegressor-hi-80 | KNeighborsRegressor-hi-95 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | H1 | 701 | 612.454151 | 615.2 | 597.550958 | 601.310692 | 604.037187 | 620.871115 | 623.597610 | 627.357344 | 599.090 | 603.20 | 609.45 | 620.95 | 627.20 | 631.310 |

| 1 | H1 | 702 | 538.415217 | 551.6 | 491.913415 | 508.094072 | 527.337321 | 549.493112 | 568.736361 | 584.917018 | 505.675 | 534.04 | 535.85 | 567.35 | 569.16 | 597.525 |

| 2 | H1 | 703 | 496.797892 | 509.6 | 458.432874 | 472.483280 | 481.705219 | 511.890565 | 521.112505 | 535.162911 | 475.020 | 488.28 | 492.70 | 526.50 | 530.92 | 544.180 |

| 3 | H1 | 704 | 462.689475 | 474.6 | 414.114933 | 435.849278 | 442.808787 | 482.570164 | 489.529672 | 511.264017 | 423.700 | 444.52 | 451.00 | 498.20 | 504.68 | 525.500 |

| 4 | H1 | 705 | 439.784731 | 451.6 | 384.182476 | 400.101658 | 419.176045 | 460.393416 | 479.467803 | 495.386986 | 394.555 | 411.28 | 428.15 | 475.05 | 491.92 | 508.645 |

Merge the test data with forecasts:

test_with_forecasts = test.merge(forecasts, how="left", on=["unique_id", "ds"])

Plot the point and the prediction intervals:

levels = [50, 80, 95]

fig = plot_series(

train,

test_with_forecasts,

plot_random=False,

models=["KNeighborsRegressor"],

level=levels,

max_insample_length=48,

palette="tab10",

)

fig.set_size_inches(8, 4)

fig

6.7.21. Sliding Window Approach to Time Series Cross-Validation#

Show code cell content

!pip install mlforecast

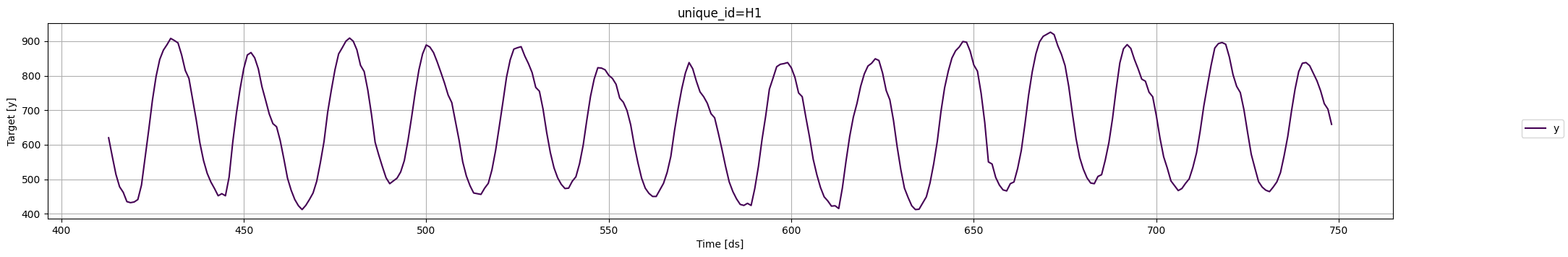

Time series cross-validation evaluates a model’s predictive performance by training on past data and testing on subsequent time periods using a sliding window approach.

MLForecast offers an efficient and easy-to-use implementation of this technique.

To see how to implement time series cross-validation with MLForecast, let’s start reading a subset of the M4 Competition hourly dataset.

import pandas as pd

from utilsforecast.plotting import plot_series

Y_df = pd.read_csv("https://datasets-nixtla.s3.amazonaws.com/m4-hourly.csv").query(

"unique_id == 'H1'"

)

print(Y_df)

unique_id ds y

0 H1 1 605.0

1 H1 2 586.0

2 H1 3 586.0

3 H1 4 559.0

4 H1 5 511.0

.. ... ... ...

743 H1 744 785.0

744 H1 745 756.0

745 H1 746 719.0

746 H1 747 703.0

747 H1 748 659.0

[748 rows x 3 columns]

Plot the time series:

fig = plot_series(Y_df, plot_random=False, max_insample_length=24 * 14)

fig

Instantiate a new MLForecast object:

from mlforecast import MLForecast

from mlforecast.target_transforms import Differences

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

mlf = MLForecast(

models=[LinearRegression()],

freq=1,

target_transforms=[Differences([24])],

lags=range(1, 25),

)

Once the MLForecast object has been instantiated, we can use the cross_validation method.

For this particular example, we’ll use 3 windows of 24 hours.

# use 3 windows of 24 hours

cross_validation_df = mlf.cross_validation(

df=Y_df,

h=24,

n_windows=3,

)

print(cross_validation_df.head())

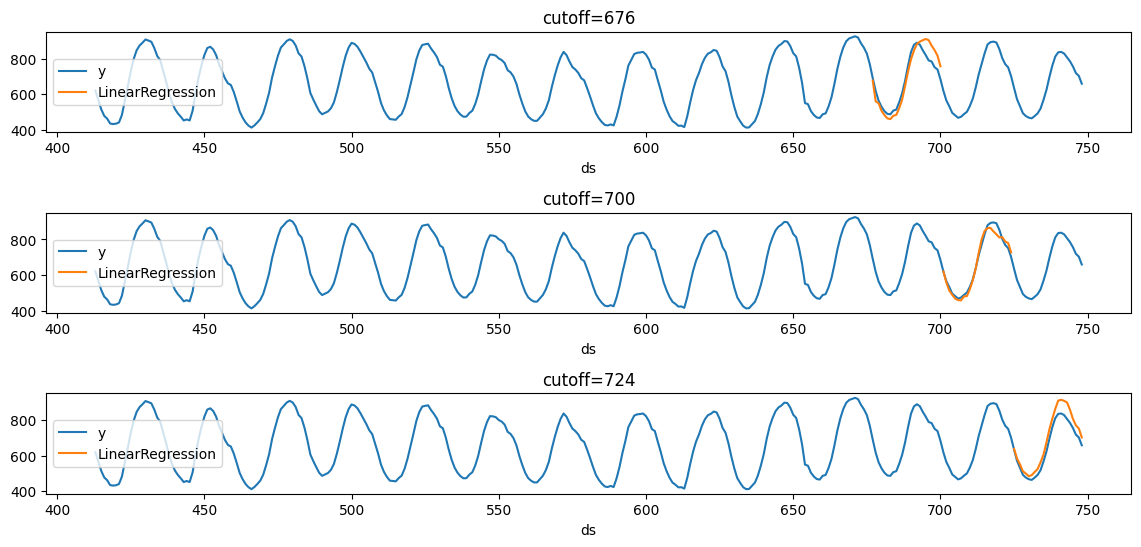

unique_id ds cutoff y LinearRegression

0 H1 677 676 691.0 676.726797

1 H1 678 676 618.0 559.559522

2 H1 679 676 563.0 549.167938

3 H1 680 676 529.0 505.930997

4 H1 681 676 504.0 481.981893

We’ll now plot the forecast for each cutoff period.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def plot_cv(df, df_cv, last_n=24 * 14):

cutoffs = df_cv["cutoff"].unique()

fig, ax = plt.subplots(

nrows=len(cutoffs), ncols=1, figsize=(14, 6), gridspec_kw=dict(hspace=0.8)

)

for cutoff, axi in zip(cutoffs, ax.flat):

df.tail(last_n).set_index("ds").plot(ax=axi, y="y")

df_cv.query("cutoff == @cutoff").set_index("ds").plot(

ax=axi,

y="LinearRegression",

title=f"{cutoff=}",

)

plot_cv(Y_df, cross_validation_df)

Notice that in each cutoff period, we generated a forecast for the next 24 hours using only the data y before said period.

6.7.22. Handling Static and Dynamic Features in Time Series Forecasting with MLForecast#

Show code cell content

!pip install mlforecast

Basic time series data often fails to properly incorporate different types of features.

MLForecast provides a comprehensive solution for handling both static and dynamic features:

import lightgbm as lgb

from mlforecast import MLForecast

from mlforecast.utils import generate_daily_series, generate_prices_for_series

## Generate sample data

series = generate_daily_series(100, equal_ends=True, n_static_features=2)

series = series.rename(columns={"static_0": "store_id", "static_1": "product_id"})

## Generate price catalog (dynamic feature)

prices_catalog = generate_prices_for_series(series)

## Merge static and dynamic features

series_with_prices = series.merge(prices_catalog, how="left")

print(series_with_prices.head(10))

unique_id ds y store_id product_id price

0 id_00 2000-10-05 39.811983 79 45 0.548814

1 id_00 2000-10-06 103.274013 79 45 0.715189

2 id_00 2000-10-07 176.574744 79 45 0.602763

3 id_00 2000-10-08 258.987900 79 45 0.544883

4 id_00 2000-10-09 344.940404 79 45 0.423655

5 id_00 2000-10-10 413.520305 79 45 0.645894

6 id_00 2000-10-11 506.990093 79 45 0.437587

7 id_00 2000-10-12 12.688070 79 45 0.891773

8 id_00 2000-10-13 111.133819 79 45 0.963663

9 id_00 2000-10-14 197.982842 79 45 0.383442

Create and train the forecasting model:

# Create MLForecast model

fcst = MLForecast(

models=lgb.LGBMRegressor(random_state=0),

freq="D",

lags=[7], # Use 7-day lag

date_features=["dayofweek"], # Add day of week as feature

)

## Fit model specifying which features are static

fcst.fit(

series_with_prices,

static_features=["store_id", "product_id"], # Specify static features

)

MLForecast(models=[LGBMRegressor], freq=D, lag_features=['lag7'], date_features=['dayofweek'], num_threads=1)

## Check which features are used for training

print("\nFeatures used for training:")

print(fcst.ts.features_order_)

Features used for training:

['store_id', 'product_id', 'price', 'lag7', 'dayofweek']

Generate predictions:

## Make predictions using future prices

predictions = fcst.predict(

h=7, X_df=prices_catalog # Forecast 7 days ahead # Provide future prices

)

print(predictions.head(10))

unique_id ds LGBMRegressor

0 id_00 2001-05-15 421.301684

1 id_00 2001-05-16 497.335181

2 id_00 2001-05-17 20.108545

3 id_00 2001-05-18 101.930145

4 id_00 2001-05-19 184.264253

5 id_00 2001-05-20 260.803990

6 id_00 2001-05-21 343.501305

7 id_01 2001-05-15 118.299009

8 id_01 2001-05-16 148.793503

9 id_01 2001-05-17 184.066779

6.7.23. Hierarchical Forecasting in Python#

Show code cell content

%%capture

!pip install hierarchicalforecast

!pip install -U statsforecast numba

In complex datasets, forecasts at detailed levels (e.g., regions, products) should align with higher-level forecasts (e.g., countries, categories). Inconsistent forecasts can lead to poor decisions.

Hierarchical forecasting ensures forecasts are consistent across all levels to reconcile and match forecasts from lower to higher levels.

HierarchicalForecast, an open-source library from Nixtla, offers tools and methods specifically designed for creating and reconciling hierarchical forecasts.

For illustrative purposes, consider a sales dataset with the following columns:

Country: The country where the sales occurred.

Region: The region within the country.

State: The state within the region.

Purpose: The purpose of the sale (e.g., Business, Leisure).

ds: The date of the sale.

y: The sales amount.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

%%capture

Y_df = pd.read_csv(

"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Nixtla/transfer-learning-time-series/main/datasets/tourism.csv"

)

Y_df = Y_df.rename({"Trips": "y", "Quarter": "ds"}, axis=1)

Y_df.insert(0, "Country", "Australia")

Y_df = Y_df[["Country", "State", "Region", "Purpose", "ds", "y"]]

Y_df["ds"] = Y_df["ds"].str.replace(r"(\d+) (Q\d)", r"\1-\2", regex=True)

Y_df["ds"] = pd.to_datetime(Y_df["ds"])

Y_df.head()

The dataset can be grouped in the following non-strictly hierarchical structure:

Country

Country, State

Country, Purpose

Country, State, Region

Country, State, Purpose

Country, State, Region, Purpose

spec = [

["Country"],

["Country", "State"],

["Country", "Purpose"],

["Country", "State", "Region"],

["Country", "State", "Purpose"],

["Country", "State", "Region", "Purpose"],

]

Using the aggregate function from HierarchicalForecast we can get the full set of time series.

from hierarchicalforecast.utils import aggregate

Y_df, S_df, tags = aggregate(Y_df, spec)

Y_df = Y_df.reset_index()

Y_df.sample(10)

| unique_id | ds | y | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12251 | Australia/New South Wales/Outback NSW/Business | 2000-10-01 | 23.780860 |

| 33131 | Australia/Western Australia/Australia's North ... | 2000-10-01 | 45.648865 |

| 22034 | Australia/South Australia/Fleurieu Peninsula/O... | 2006-07-01 | 0.000000 |

| 31119 | Australia/Victoria/Phillip Island/Visiting | 2017-10-01 | 58.063034 |

| 7671 | Australia/New South Wales/Other | 2015-10-01 | 405.891206 |

| 18339 | Australia/Queensland/Mackay/Business | 2002-10-01 | 54.135284 |

| 23043 | Australia/South Australia/Limestone Coast/Visi... | 1998-10-01 | 32.604546 |

| 22129 | Australia/South Australia/Fleurieu Peninsula/V... | 2010-04-01 | 44.738053 |

| 11349 | Australia/New South Wales/Hunter/Business | 2015-04-01 | 132.226040 |

| 16599 | Australia/Queensland/Brisbane/Other | 2007-10-01 | 70.490809 |

Get all the distinct ‘Country/Purpose’ combinations present in the dataset:

tags["Country/Purpose"]

array(['Australia/Business', 'Australia/Holiday', 'Australia/Other',

'Australia/Visiting'], dtype=object)

We use the final two years (8 quarters) as test set.

Y_test_df = Y_df.groupby("unique_id").tail(8)

Y_train_df = Y_df.drop(Y_test_df.index)

Y_test_df = Y_test_df.set_index("unique_id")

Y_train_df = Y_train_df.set_index("unique_id")

Y_train_df.groupby("unique_id").size()

unique_id

Australia 72

Australia/ACT 72

Australia/ACT/Business 72

Australia/ACT/Canberra 72

Australia/ACT/Canberra/Business 72

..

Australia/Western Australia/Experience Perth/Other 72

Australia/Western Australia/Experience Perth/Visiting 72

Australia/Western Australia/Holiday 72

Australia/Western Australia/Other 72

Australia/Western Australia/Visiting 72

Length: 425, dtype: int64

The following cell generates base forecasts for each time series in Y_df using the ETS model. The forecasts and fitted values are stored in Y_hat_df and Y_fitted_df, respectively.

%%capture

from statsforecast.core import StatsForecast

from statsforecast.models import ETS

fcst = StatsForecast(

df=Y_train_df, models=[ETS(season_length=4, model="ZZA")], freq="QS", n_jobs=-1

)

Y_hat_df = fcst.forecast(h=8, fitted=True)

Y_fitted_df = fcst.forecast_fitted_values()

Since Y_hat_df contains forecasts that are not coherent—meaning forecasts at detailed levels (e.g., by State, Region, Purpose) may not align with those at higher levels (e.g., by Country, State, Purpose)—we will use the HierarchicalReconciliation class with the BottomUp approach to ensure coherence.

from hierarchicalforecast.core import HierarchicalReconciliation

from hierarchicalforecast.methods import BottomUp

reconcilers = [BottomUp()]

hrec = HierarchicalReconciliation(reconcilers=reconcilers)

Y_rec_df = hrec.reconcile(Y_hat_df=Y_hat_df, Y_df=Y_fitted_df, S=S_df, tags=tags)

The dataframe Y_rec_df contains the reconciled forecasts.

Y_rec_df.head()

| ds | ETS | ETS/BottomUp | |

|---|---|---|---|

| unique_id | |||

| Australia | 2016-01-01 | 25990.068359 | 24380.257812 |

| Australia | 2016-04-01 | 24458.490234 | 22902.765625 |

| Australia | 2016-07-01 | 23974.056641 | 22412.982422 |

| Australia | 2016-10-01 | 24563.455078 | 23127.439453 |

| Australia | 2017-01-01 | 25990.068359 | 24516.759766 |

6.7.24. Generative Pre-trained Forecasting with TimeGPT#

Show code cell content

!pip install nixtla

TimeGPT is a powerful generative pre-trained forecasting model that can generate accurate forecasts for new time series without the need for training. TimeGPT can be used across a variety of tasks including demand forecasting, anomaly detection, financial forecasting, and more.

from nixtla import NixtlaClient

nixtla_client = NixtlaClient(api_key="my_api_key_provided_by_nixtla")

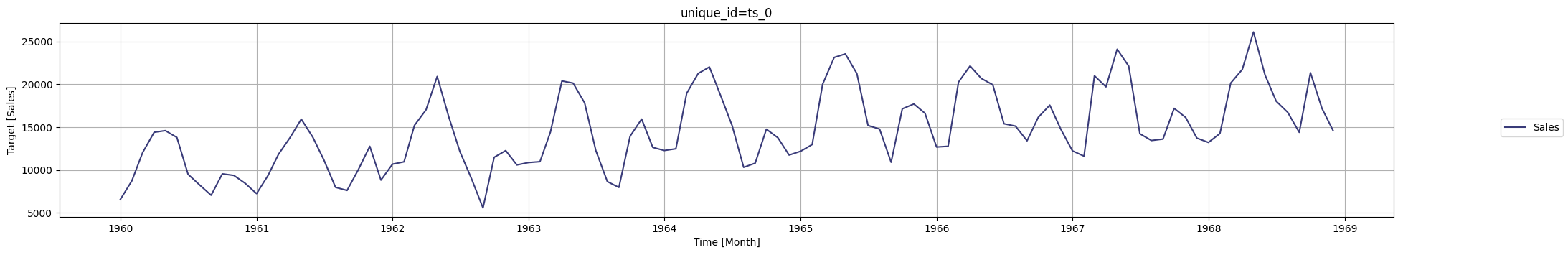

import pandas as pd

time_column = "Month"

value_column = "Sales"

df = pd.read_csv(

"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jbrownlee/Datasets/master/monthly-car-sales.csv",

parse_dates=[time_column],

)

df.head()

| Month | Sales | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1960-01-01 | 6550 |

| 1 | 1960-02-01 | 8728 |

| 2 | 1960-03-01 | 12026 |

| 3 | 1960-04-01 | 14395 |

| 4 | 1960-05-01 | 14587 |

nixtla_client.plot(df, time_col=time_column, target_col=value_column)

timegpt_fcst_df = nixtla_client.forecast(

df=df, h=12, freq="MS", time_col=time_column, target_col=value_column

)

timegpt_fcst_df.head()

INFO:nixtla.nixtla_client:Validating inputs...

INFO:nixtla.nixtla_client:Preprocessing dataframes...

INFO:nixtla.nixtla_client:Restricting input...

INFO:nixtla.nixtla_client:Calling Forecast Endpoint...

| Month | TimeGPT | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1969-01-01 | 14672.101562 |

| 1 | 1969-02-01 | 15793.253906 |

| 2 | 1969-03-01 | 21517.191406 |

| 3 | 1969-04-01 | 22996.332031 |

| 4 | 1969-05-01 | 25959.019531 |

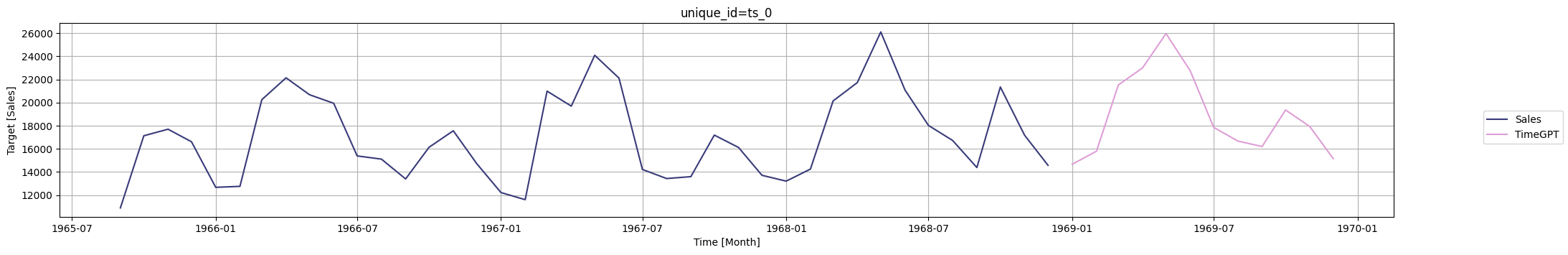

nixtla_client.plot(

df,

timegpt_fcst_df,

time_col=time_column,

target_col=value_column,

max_insample_length=40,

)

6.7.25. Automate Time Series Feature Engineering with tsfresh#

Show code cell content

!pip install tsfresh

Data scientists spend much of their time cleaning data or building features. While the former is unavoidable, the latter can be automated.

tsfresh uses a robust feature selection algorithm to automatically extract relevant time series features, freeing up data scientists’ time.

To demonstrate this, start with loading an example dataset:

from tsfresh.examples.robot_execution_failures import (

download_robot_execution_failures,

load_robot_execution_failures,

)

download_robot_execution_failures()

timeseries, y = load_robot_execution_failures()

timeseries.head()

| id | time | F_x | F_y | F_z | T_x | T_y | T_z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 63 | -3 | -1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 62 | -3 | -1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | -1 | -1 | 61 | -3 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | -1 | -1 | 63 | -2 | -1 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 4 | -1 | -1 | 63 | -3 | -1 | 0 |

Extract features and select only relevant features for each time series.

from tsfresh import extract_relevant_features

# extract relevant features

features_filtered = extract_relevant_features(

timeseries, y, column_id="id", column_sort="time"

)

Feature Extraction: 100%|██████████| 20/20 [00:05<00:00, 3.83it/s]

You can now use the features in features_filtered to train your classification model.

# perform model training with the extracted features

6.7.26. tsmoothie: Fast and Flexible Tool for Exponential Smoothing#

Show code cell content

pip install --upgrade tsmoothie

Exponential smoothing is useful for capturing the underlying pattern in the data, especially for data with a strong trend or seasonal component.

tsmoothie is designed to be fast and efficient and provides a wide range of smoothing techniques.

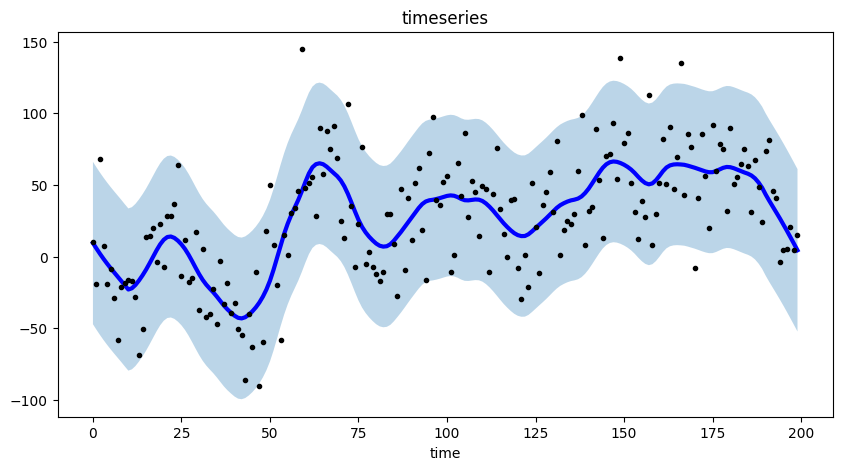

To see how tsmoothie works, let’s generate a single random walk time series of length 200 using the sim_randomwalk() function.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from tsmoothie.smoother import LowessSmoother

from tsmoothie.utils_func import sim_randomwalk

# generate a random walk of length 200

np.random.seed(123)

data = sim_randomwalk(n_series=1, timesteps=200, process_noise=10, measure_noise=30)

Next, create a LowessSmoother object with a smooth_fraction of 0.1 (i.e., 10% of the data points are used for local regression) and 1 iteration. We then apply the smoothing operation to the data using the smooth() method.

# operate smoothing

smoother = LowessSmoother(smooth_fraction=0.1, iterations=1)

smoother.smooth(data)

<tsmoothie.smoother.LowessSmoother>

After smoothing the data, we use the get_intervals() method of the LowessSmoother object to calculate the lower and upper bounds of the prediction interval for the smoothed time series.

# generate intervals

low, up = smoother.get_intervals("prediction_interval")

Finally, we plot the smoothed time series (as a blue line), and the prediction interval (as a shaded region) using matplotlib.

# plot the smoothed time series with intervals

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

plt.plot(smoother.smooth_data[0], linewidth=3, color="blue")

plt.plot(smoother.data[0], ".k")

plt.title(f"timeseries")

plt.xlabel("time")

plt.fill_between(range(len(smoother.data[0])), low[0], up[0], alpha=0.3)

<matplotlib.collections.PolyCollection at 0x15b25a8e0>

This graph effectively highlights the trend and seasonal components present in the time series data through the use of a smoothed representation.

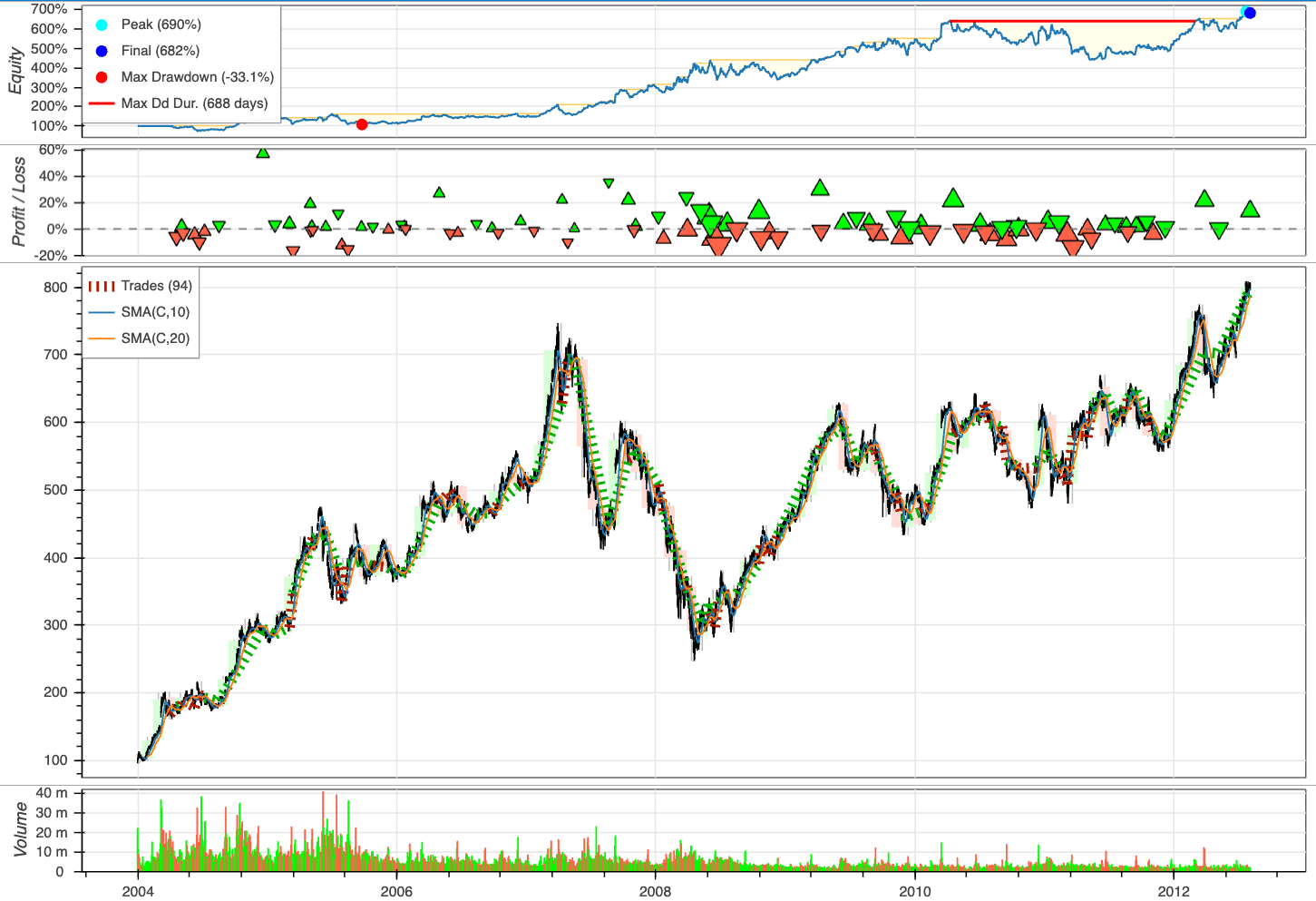

6.7.27. Backtesting: Assess Trading Strategy Performance Effortlessly in Python#

Show code cell content

!pip install -U backtesting

Evaluating trading strategies’ effectiveness is crucial for financial decision-making, but it’s challenging due to the complexities of historical data analysis and strategy testing.

Backtesting allows users to simulate trades based on historical data and visualize the outcomes through interactive plots in three lines of code.

To see how Backtesting works, let’s create our first strategy to backtest on these Google data, a simple moving average (MA) cross-over strategy.

from backtesting.test import GOOG

print(GOOG.tail())

Open High Low Close Volume

2013-02-25 802.3 808.41 790.49 790.77 2303900

2013-02-26 795.0 795.95 784.40 790.13 2202500

2013-02-27 794.8 804.75 791.11 799.78 2026100

2013-02-28 801.1 806.99 801.03 801.20 2265800

2013-03-01 797.8 807.14 796.15 806.19 2175400

import pandas as pd

def SMA(values, n):

"""

Return simple moving average of `values`, at

each step taking into account `n` previous values.

"""

return pd.Series(values).rolling(n).mean()

from backtesting import Strategy

from backtesting.lib import crossover

class SmaCross(Strategy):

# Define the two MA lags as *class variables*

# for later optimization

n1 = 10

n2 = 20

def init(self):

# Precompute the two moving averages

self.sma1 = self.I(SMA, self.data.Close, self.n1)

self.sma2 = self.I(SMA, self.data.Close, self.n2)

def next(self):

# If sma1 crosses above sma2, close any existing

# short trades, and buy the asset

if crossover(self.sma1, self.sma2):

self.position.close()

self.buy()

# Else, if sma1 crosses below sma2, close any existing

# long trades, and sell the asset

elif crossover(self.sma2, self.sma1):

self.position.close()

self.sell()

To assess the performance of our investment strategy, we will instantiate a Backtest object, using Google stock data as our asset of interest and incorporating the SmaCross strategy class. We’ll start with an initial cash balance of 10,000 units and set the broker’s commission to a realistic rate of 0.2%.

from backtesting import Backtest

bt = Backtest(GOOG, SmaCross, cash=10_000, commission=0.002)

stats = bt.run()

stats

Start 2004-08-19 00:00:00

End 2013-03-01 00:00:00

Duration 3116 days 00:00:00

Exposure Time [%] 97.067039

Equity Final [$] 68221.96986

Equity Peak [$] 68991.21986

Return [%] 582.219699

Buy & Hold Return [%] 703.458242

Return (Ann.) [%] 25.266427

Volatility (Ann.) [%] 38.383008

Sharpe Ratio 0.658271

Sortino Ratio 1.288779

Calmar Ratio 0.763748

Max. Drawdown [%] -33.082172

Avg. Drawdown [%] -5.581506

Max. Drawdown Duration 688 days 00:00:00

Avg. Drawdown Duration 41 days 00:00:00

# Trades 94

Win Rate [%] 54.255319

Best Trade [%] 57.11931

Worst Trade [%] -16.629898

Avg. Trade [%] 2.074326

Max. Trade Duration 121 days 00:00:00

Avg. Trade Duration 33 days 00:00:00

Profit Factor 2.190805

Expectancy [%] 2.606294

SQN 1.990216

_strategy SmaCross

_equity_curve ...

_trades Size EntryB...

dtype: object

Plot the outcomes:

bt.plot()

6.7.28. Chronos: Unleashing Pre-trained Language Models for Time Series Forecasting#

Show code cell content

!pip install git+https://github.com/amazon-science/chronos-forecasting.git

Probabilistic time series forecasting helps data scientists and analysts predict future values with uncertainty estimates. To leverage pre-trained language models for accurate time series predictions, use Chronos.

The power of Chronos lies in its ability to generate accurate forecasts right out of the box, eliminating the need for extensive model training or fine-tuning in many cases.

Here’s a quick example of using Chronos for forecasting:

import pandas as pd

import torch

from chronos import ChronosPipeline

pipeline = ChronosPipeline.from_pretrained(

"amazon/chronos-t5-small", torch_dtype=torch.bfloat16

)

df = pd.read_csv(

"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/AileenNielsen/TimeSeriesAnalysisWithPython/master/data/AirPassengers.csv"

)

# forecast shape: [num_series, num_samples, prediction_length]

forecast = pipeline.predict(

context=torch.tensor(df["#Passengers"]), prediction_length=12, num_samples=20

)

This code loads the air passenger data, uses the pretrained Chronos model to generate 20 possible forecasts for the next 12 months, and then calculates the median forecast along with a 90% prediction interval.

The Chronos model internally transforms the numerical time series into tokens, processes them through a language model architecture, and then converts the output back into numerical forecasts. This approach allows it to capture complex patterns and dependencies in the data, potentially outperforming traditional forecasting methods, especially in zero-shot scenarios where the model hasn’t been specifically trained on the target time series.